Send in the Critics: The Crisis of Confidence at the New York Times

The New York Times has become the news again. Twice in the past week, its own readers angrily criticized the newspaper — and with powerful irony — for a perceived pro-Trump bias.

Early in the week, the Times published a story under the headline, “As Chaos Spreads, Trump Vows to ‘End It Now’”. Later in the week, the paper published an op-ed piece by Senator Tom Cotton titled “Send in the Troops Now”, calling on Trump to use military force against protestors in the streets of the nation. This time the reaction was explosive — not only amongst Times readers, but also in the newsroom.

In damage control mode, Times senior management frantically attempted to put out the fire, at first with a statement admitting to an editorial process failure. That didn’t satisfy critics. Faced with a staff walkout, top Times editors switched tactics and came clean with humbling mea culpa and promised to change the way the Opinion pages are managed.

This controversy is about more than editorial processes inside the New York Times. It’s a symptom of a deeper media malaise with far-reaching consequences for professional journalism, especially in the United States. American newspapers, unlike their partisan British counterparts, have long cherished professional values of fact, impartiality, objectivity, fairness —and diversity of opinion. But these values have been severely eroded over the past decade. American journalism is increasingly becoming, like feisty British papers, more engaged, opinionated, partisan, even politicized.

There are two main explanations for this partisan turn. First, the arrival in newsrooms of a young generation with activist and partisan values that challenge established professional practices based on facts and objectivity. Some have observed that the “culture wars” once confined to university campuses have stormed the mainstream media fortress. Second, journalism’s new business model (relying more on subscriptions than on advertising) is driving newspapers and magazines towards more engaged and partisan positions as they seek to satisfy and retain their paying customers.

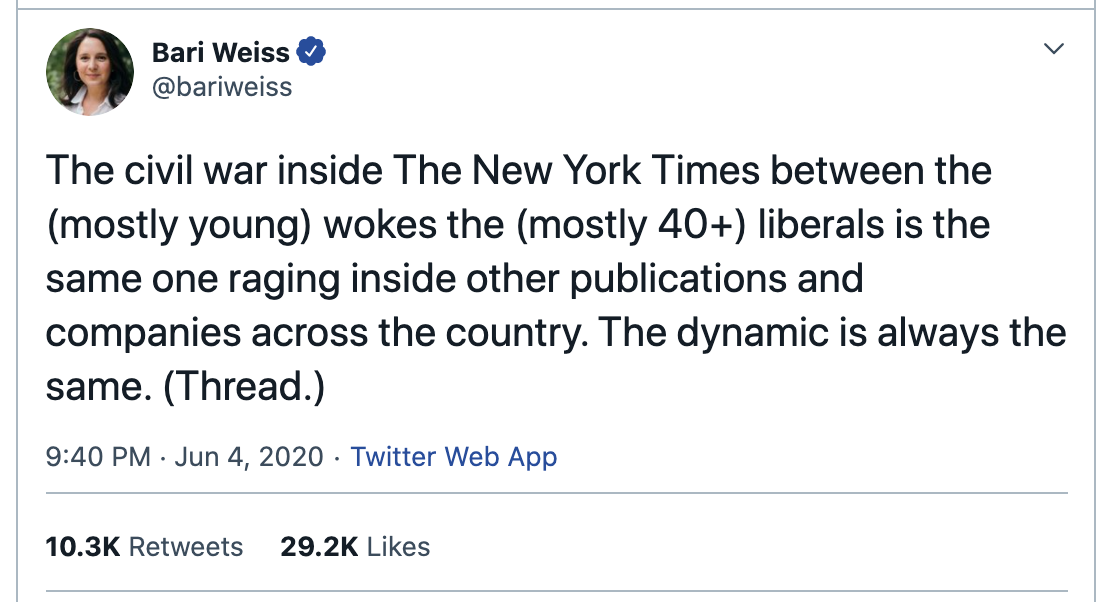

On the first point, the “culture wars” argument was made this week by a columnist inside the New York Times. Bari Weiss, a Times op-ed writer, observed in a series of tweets that a “civil war” opposing two generational camps was raging inside the newspaper. On one side, young “woke” staffers who advocate the right to feel emotionally and psychologically “safe”. On the other side, older journalists who, while liberal minded and progressive, espouse established professional values. “Here’s one way to think about what’s at stake,” noted Weiss. “The New York Times motto is ‘all the news that’s fit to print.’ One group emphasizes the word ‘all’. The other, the word ‘fit’.”

Weiss argued that this clash finds its origins in the hiring of young journalists fresh from the campus culture wars. “I’ve been mocked by many people over the past few years for writing about the campus culture wars,” she noted. “They told me it was a sideshow. But this was always why it mattered: The people who graduated from those campuses would rise to power inside key institutions and transform them.” Weiss’s opinion was dismissed on Twitter as wildly exaggerated or just plain wrong. Others supported her view, saying what she described was an accurate assessment of the current state of the New York Times newsroom.

Leaving that dispute aside, Weiss’s observation was not particularly controversial. The executive editor of the New York Times has said as much. Dean Baquet has stated in interviews that managing the new generation of journalists is challenging because they bring partisan baggage with them — especially regarding Donald Trump. “I make it very clear when I hire, I make it very clear when I talk to the staff, I’ve said it repeatedly, that we are not supposed to be the leaders of the resistance to Donald Trump,” Baquet said. “That is an untenable, non-journalistic, immoral position for the New York Times.” Baquet repeated this view in the wake of the scandal that rocked the newspaper this past week.

New York Times op-ed columnist Bari Weiss tweeted about the controversy.

Baquet’s predecessor, Jill Abramson, made the same observation in her book, Merchants of Truth, when assessing the newspaper’s coverage of the 2016 presidential election. She observed that her former employer had become “unmistakably anti-Trump.” Abramson praised some aspects of the Times’s coverage of Trump. She noted, however, that, while the paper claimed it didn’t want to set itself up as an “opposition party”, headlines and news stories contained “raw opinion.”

“Given its mostly liberal audience, there was an implicit financial reward for the Times in running lots of Trump stories, almost all of them negative,” wrote Abramson. “They drove big traffic numbers and, despite the blip of cancellations after the election, inflated subscription orders to levels no one anticipated. But the more anti-Trump the Times was perceived to be, the more it was mistrusted for being biased.” Abramson added that young “woke” Times staffers favoured a more adversarial stance vis-à-vis Trump because “urgent times called for urgent measures; the dangers of Trump’s presidency obviated the old standards.”

The “old standards” prevailed in American journalism throughout most of the past century. Unlike journalism in Europe, which largely remained attached to partisan politics, American journalism professionalized a century ago. This was not a historical accident. In the early twentieth century, new professions were pushing out amateurs and asserting monopoly control over spheres of knowledge based on credentials, expertise, and ethical standards. Journalism in America became part of this movement. The University of Missouri opened its School of Journalism in 1908, followed by Columbia University in 1912. These schools inculcated new empirical values and practices in the presentation of fact-based news as objective truth. In Britain, by contrast, journalism remained an amateur vocation (dominated by Oxbridge elites) and journalism schools emerged much later.

In the United States, journalists asserted themselves as confident professionals who stood above social and political divisions. The economics of the newspaper industry helped boost this professional self-assurance. In the second half of the century, an immensely profitable business model based on advertising provided the profession with autonomy from both partisan politics and reader pressures. American journalists upheld values of facts and objectivity without fear or favour. True, there were constant pressures from advertisers and PR flaks, but the model largely worked to transform American journalism into a “fourth estate”. The profession’s “high-modernist” period, as it has been called, was unique to the United States where there was a broad political consensus and limited ideological diversity around accepted facts and values. The Watergate scandal in the early 1970s marked the apogee of the “high modernist” era. In the wake of Watergate — and the Hollywood film about the scandal, All the President’s Men — the profession became glamorous and enrolment at American journalism schools soared.

New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet (photo: New York Times).

Over the next few decades, however, American journalism was transformed by factors that gradually challenged these professional values and practices. The emergence of round-the-clock cable TV channels triggered a major revolution in the news business. Competition for viewers was cut-throat, so cable channels produced face-paced news with high-volume opinion. Another factor was the emergence of so-called “New Journalism” emphasizing first-person narratives and fictional techniques, especially in magazine writing. This was part of the wider postmodern zeitgeist that contested established values about objective truth. Critics like Noam Chomsky, meanwhile, argued that the objectivity in journalism was a myth to begin with. For Chomsky, the media were the glove-puppets of their corporate masters.

Finally, and most importantly, the social media explosion circa 2010 destroyed the advertising-driven business model that had financed and strengthened professional journalism. Newspapers and magazines were slow to respond to the challenge of the digital revolution, and paid a high price for their stubborness. Today, the lion’s share of advertising revenues has been siphoned by two internet giants: Google and Facebook. Together, they control more than 60 percent of global online advertising revenue. This drained away the robust revenues on which newspapers and magazines depended for decades — and produced devastating consequences for professional journalism. Today, many are frantically attempting to recapture lost revenues with sponsored content, native advertising, event marketing, and retooling editorial strategies based on gaming the algorithms of Facebook and Google.

Some newspapers and magazines, including the New York Times, have managed to thrive by shifting away from advertising revenues and focusing on paid digital subscriptions. The Times, in particular, has been hugely successfully in driving new digital subscribers, reaching more than five million today. Subscriptions began to soar after Donald Trump’s election victory in 2016 — so much so that the newspaper’s financial success was dubbed a “Trump bump”. Millions of new subscribers generated massive cash flow for the newspaper. But the sudden boom in digital subscribers also set up expectations amongst paid-up customers about the newspapers politics. Overwhelmingly, Times subscribers are anti-Trump — and many expect the newspaper to reflect their views.

Google and Facebook control more than 60% of global online advertising revenue.

This brings us back to the two points raised above — namely, that the New York Times isn’t being reshaped only by “culture wars” in its own newsroom, its successful subscription-driven business model is also putting political pressures on the newspaper. As noted above, in the past newspapers enjoyed relative autonomy — from both partisan politics and reader pressures — thanks to robust revenues from advertising. Readers didn’t have much of a voice in editorial matters of newspapers and magazines. True, they could cancel a subscription, but print journalism was so profitable thanks to advertising that journalists could be largely impervious to reader complaints. Today, however, the advertising revenue has vanished. Newspapers and magazines now must be hyper-sensitive to their readers because they are paying the bills. And today in the Trump era, they have strong political views.

Media critic Jay Rosen identified this trend in 2018 on his PressThink blog: “The readers of the New York Times have more power now. They have more power because they have more choices. And because the internet, where most of the reading happens, is inherently two-way. Also because Times journalists are now exposed to opinion and reaction on social media. And especially because readers are paying more of the costs. Their direct payments are keeping the Times afloat. This will be increasingly so in the future, as the advertising business gets absorbed by the tech industry. The Times depends on its readers’ support more than it ever has.”

Some at the New York Times undoubtedly embrace this trend towards journalism driven by partisan loyalties and activist values. But it clearly doesn’t sit well with some senior editors, including executive editor Dan Baquet who has warned against pandering to readers. When the Washington Post adopted “Democracy dies in darkness” as the newspaper’s engagé motto, Baquet remarked that it “sounds like the next Batman movie”. He told his staff this week: “I think some news organizations have gone a little bit far — not about Trump — but to please an audience.”

Baquet is defending the “high modernist” professional values and practices that prevailed in American journalism for the past half century. But the old mainstream media fortress is under siege. Over the past decade, journalism has been “de-professionalized” by new technologies and social media. Media have become more activist and partisan. A new generation of journalists raised in a cultural zeitgeist hostile to objective truths is moving up the ranks of the mainstream media. They are also subscribing to newspapers and magazines and expect them to advocate for their own political agenda — whether on the left or right.

American journalists may still not be as openly partisan as their European counterparts, but the trend appears to be moving in that direction. The old guard will continue to defend established values, standards, and practices. But the impetus towards politicization will likely accelerate in the coming years. In many respects, newspapers and magazines are becoming digital-era versions of the old pamphlets and papers in the eighteenth century when partisan allegiances were openly proclaimed.

Matthew Fraser is a former newspaper correspondent in London and Paris, and subsequently was media industries columnist and Editor-in-Chief of the National Post. Currently a professor at the American University of Paris, his new book is In Truth: A History of Lies from Ancient Rome to Modern America. This column has also been published here on Medium.