Sir Robert Walpole’s Kidney Stones

We learned last week that Sir Isaac Newton, perhaps the greatest scientific mind of the Enlightenment, came up with a cure for the plague: toad vomit.

The plague was very much on Newton’s mind in 1667 when he hit upon his cure. Over the previous two years, the pestilence had wiped out a large portion of London’s population, roughly 100,000 people. Newton’s proposed remedy does not appear to have advanced beyond his Cambridge notebooks. But he lived at a time when many outlandish nostrums were promoted as bone fide cures for every imaginable disease.

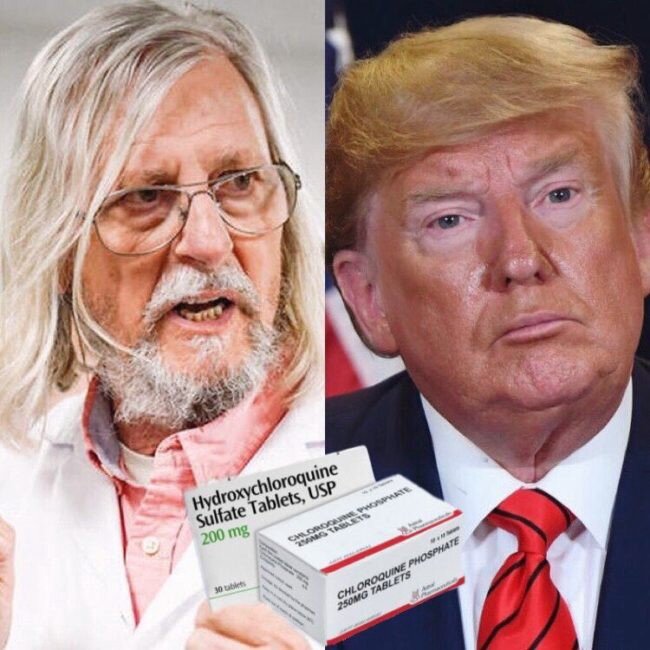

More than three centuries later, the idea of toad vomit to cure bubonic plague undoubtedly seems bizarrely archaic. Yet the coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated that, in times of crisis, we are just as eager to put faith in questionable remedies for deadly disease. One of them is hydroxychloroquine, advocated by the flamboyant French microbiologist Dr Didier Raoult. Some believe the anti-malaria drug is effective treatment against Covid-19. Others dismiss Dr Raoult as a dangerous eccentric and warn that the drug poses serious health risks.

Besides Dr Raoult, hydroxychloroquine has a powerful endorser in Donald Trump. He claimed to be taking the drug to fortify himself against the virus. Trump also caused widespread alarm when he suggested that injecting disinfectant could kill the virus. In Spain, meanwhile, a coastal resort town sprayed the local beach with bleach in an attempt to protect children from the coronavirus.

Dr Didier Raoult and Donald Triump endorse hydroxychloroquine as a treatment against Covid-19.

Donald Trump isn’t the first powerful political figure to find comfort in a controversial medicine. Faith in bogus cures has a long and controversial history, even in the highest spheres of society.

Britain’s first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, stands out in history amongst powerful figures taken in by a quack remedy. Walpole bestrode British politics like a colossus during the first half of the eighteenth century. He dominated the political stage for three decades at the height of the Enlightenment, an epoch marked by great achievements in philosophy, literature, and science. Yet the advances of science were powerless to cure the chronic ailment that caused Walpole unbearable pain: kidney stones.

In Walpole’s day, available treatments were limited for “the stone”, as it was known, probably caused by high animal protein in diets. One option was surgery, though it was dangerous with a high mortality rate from hemorrhage or septicemia. Walpole turned instead to medical remedies in the hope of dissolving his kidney stones. This was equally perilous, however, for the eighteenth century was a great age of quackery. London was crawling with dubious medical practitioners peddling bogus nostrums. A popular cure-all remedy was tar water, consisting of one quart of tar stirred into a gallon of water. Tar water was widely believed to cure everything from smallpox to scurvy and typhus.

One of the most famous medical miracle workers of that era was herbalist Miss Joanna Stephens. She successfully promoted a medicine that, she claimed, dissolved kidney stones, or vesical calculi. Miss Stephens, it is true, had many detractors who denounced her as a fraud flogging bogus cures. But she enjoyed the support of many eminent physicians and powerful figures at the highest levels of the British establishment.

Britain’s first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, stands out in history amongst powerful figures taken in by a quack remedy.

Such was Miss Stephens’ renown as a respected medical “empiric” that, in 1739, the British Parliament offered her £5,000 — a substantial sum in the eighteenth century — to make known the ingredients of her famous kidney stone cure. Her remedy, fabricated in pill form, was a concoction consisting primarily of Alicant soap and calcined egg shells. Sometimes limewater was used in the treatment.

To dispel doubts and justify the extraordinary payment offered to Miss Stephens, many tests by distinguished medical experts were completed to verify the effectiveness of her remedy. All concluded that her cure for the stone worked. Her medicine was hailed as being “of great Importance to Mankind”. Not surprisingly, Sir Robert Walpole tried the treatment for his chronic stones. Feeling greatly improved, he swore by Miss Stephens’ cure.

Superstition, credulity, and irrational belief in bogus cures have a long history. The ancient Romans were highly rational and accomplished magnificent feats in science and engineering, yet when it came to medicine they were strangely superstitious. Quack doctors thrived in Rome. Fortune-tellers foretold the future in the entrails of frogs. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the medieval age carried forward the ancient Hippocratic notion of four humors — blood, bile, phlegm, black bile — and the belief that disease was carried by “miasma”, or foul air. Medieval astrologers armed with star charts were often consulted to explain illnesses.

William Harvey’s discovery of blood circulation in 1628 marked a huge advance in medical knowledge. Still, superstitious and quackery were pervasive throughout the Enlightenment. When Daniel Defoe published A Journal of the Plague Year in 1722, Sir Robert Walpole had only recently become prime minister under George I. In Defoe’s book on the Great Plague of London, a work of fiction masquerading as fact, he took aim at the frauds of his own day by denouncing “quacks and mountebanks” selling their potions as a cure for the plague.

Another common medical treatment was the ancient practice of bloodletting. In America, when George Washington was on his deathbed in December 1799, he was subjected to an excruciating bloodletting procedure that drained away about forty percent of his blood volume. Although Washington’s official cause of death was epiglottitis, or inflammation of the throat, the massive bloodletting almost certainly hastened his expiry. It did nothing, in any event, to prevent it.

The century following Washington’s death was the great era of fraudulent medical claims. In late nineteenth century America, snakeskin oil salesmen hyped an outlandish assortment of drugs and concoctions as tonics for numerous illnesses. Most famously, Coca-Cola and toothache drops contained cocaine, and heroin was included in cough medicine. Later, radium was put in toothpaste.

When the influenza pandemic struck in 1918, widespread fear triggered another boom in fraudulent cures. Many believed that eating onions offered protection from the virus. Others desperately turned to known medicines, such as morphine, belladonna, strychnine, chloroform, quinine, and camphor. More alarming was kerosene mixed with sugar. Products like Vick’s Vaporub and Formamint antiseptic lozenges were also popular (“Suck a tablet whenever you enter a crowded germ-laden place”). None of them worked.

Today, the same culture of quackery and credulity persists as people desperately search for protection against the coronavirus. It could be argued that Dr Didier Raoult is our pandemic-era Miss Joanna Stephens, while Donald Trump is cast in the role of Sir Robert Walpole. While the world awaits a vaccine, a culture of superstition continues to reject science. In China, the communist regime authorised bear bile as a cure for coronavirus. Those in the anti-vaxxer movement, meanwhile, are warning against the dangers of a vaccine. In the final analysis, the credulous who are duped by bogus cures have a common motive with religiously-motivated anti-vaxxers who reject science: fear of mortality. The former desperately turn to remedies to keep away the Grim Reaper; the latter put their faith in God.

In the end, kidney stones killed Sir Robert Walpole. He may have felt cured by Miss Stephens’s remedy, but her remedy of egg shells and soap did nothing to dissolve his stones. When Walpole died on March 18, 1745, a post mortem discovered a blood-clotted bladder and kidney stones. It was calculated that, in his futile attempts to dissolve his stones, Walpole had consumed as much as 180 pounds of soap. Miss Stephens, meanwhile, had vanished into comfortable obscurity with her generous financial windfall.