Bonfire of the Insanities: Trump and Savonarola

Donald Trump and evangelical leaders praying in the Oval Office.

While Washington D.C. burns, Donald Trump isn’t fiddling — he’s tweeting. Yet Trump briefly emerged from his White House bunker to attend church and pose with a Bible while police dispersed angry protestors with tear gas.

These are the two faces of Donald Trump, both iconic: unhinged emperor and pious president. Each one inspires different emotions amongst his opponents and supporters. In the former camp, he is frequently compared with Caligula, sometimes with Nero. The image of mad emperor evokes the tragic consequences of exalted folly — narcissism, megalomania, cruelty, even insanity. Trump’s evangelical followers, on the other hand, see in their leader the image of a different ancient ruler: the Biblical king Cyrus who delivered God’s chosen people from their Babylonian captivity.

Trump’s Cyrus cult amongst fundamentalist Christians draws a direct link between him and another, equally controversial, figure from history: Girolamo Savonarola. Famous in popular culture for his bonfires of vanities, the ill-fated Renaissance monk who whipped up mass delirium in fifteenth-century Florence holds many lessons for our own era of populist religious passions in Trump’s America.

Donald Trump: mad emperor?

Trump’s detractors see him as a mad Roman emperor, but his devoted evangelical followers see another figure from ancient history: the great Biblical hero, King Cyrus.

Savonarola, like Trump, rose to power by fulminating against corrupt elites, in his day the Medici dynasty and popes in Rome. Savonarola promised to deliver the people of Florence from the orgy of humanist decadence in Renaissance Italy. For his fanatical followers, he was a new King Cyrus, the great Persian ruler from the Old Testament who liberated the Jews from Babylonia. In fifteenth-century Italy, the zeitgeist was ready for a figure like Savonarola. Florence was at the centre of the Italian Renaissance, marked by a great flourishing of humanist learning and artistic creation under the patronage of rich benefactors such as the Medicis, who attracted to Florence the greatest artists of the day including Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. The popes, too, commissioned works by Botticelli, Perugino, and Rosselli. It also an epoch of extravagance, corruption, and violence.

Savonarola began attracting notoriety for his enflamed sermons against the worldly excesses he saw everywhere. In Florence’s Duomo cathedral, where he drew enraptured audiences of 15,000, he must have been an extraordinary sight: gaunt expression, angular features, aquiline nose, eyes burning with intensity. Electrified worshippers wept and wailed as the firebrand monk exhorted Florentines to take Christ as their king and prophesied that a ‘new Cyrus’ was coming over the mountains to scourge Italy of its sins and purify the corrupt Roman papacy.

Savonarola

Famous in popular culture for his bonfires of vanities, the ill-fated Renaissance monk who whipped up mass delirium in fifteenth-century Florence holds many lessons for our own era of populist religious passions in Trump’s America.

Savonarola’s sermons resonated powerfully in a religious culture where life was regarded as pain, misery, and suffering. A reminder was the Black Death. The plague, which had arrived in Italy in the mid-fourteenth century, decimated roughly half of Europe’s population and provoked catastrophic social upheaval. In Florence, it killed half the city’s population of 100,000. This plague’s trail of death created the cultural conditions that made many Florentines receptive to Savonarola’s apocalyptical message.

Savonarola, above all, astonished his devotees with his power of prophecy. He declared that the two most powerful men in Italy — Lorenzo de’ Medici and Pope Innocent VIII — would die in the year 1492. Both prophecies came true. Lorenzo de’ Medici, though only forty-three, suddenly fell ill and expired on April 9, 1492. A few months later, Pope Innocent fell into a terrible fever and died. For any doubters, it was now obvious to all that Savonarola was a true prophet sent by God.

Savonarola also shrewdly exploited the newly-invented printing press — much like Donald Trump uses Twitter today — as a powerful platform for his tirades. He packaged his fiery sermons into one-sheet tracts and published them straight away. Thanks to his published tracts, he quickly became one of the most widely read authors throughout Europe. The printing press put Savonarola on the vanguard of a media revolution that would soon shake the foundations of the Catholic Church.

Savonarola’s greatest coup was saving Florence from destruction. In 1494, the French king Charles VIII invaded Italy with an army 25,000 men to make his claim on the crown of Naples. The French troops plundered Tuscany and drove the Medicis from Florence. Fearless, Savonarola requested a tête-à-tête with the French king. Charles VIII, a young king only twenty-four years old, agreed to receive the famous and much older Italian priest. At their meeting in Pisa, Savonarola hailed the French king as the ‘new Cyrus’ who had come to delivery Italy from the corrupt establishment of Medicis and popes. The young French monarch was impressed. It was thanks to Savonarola’s intercession that Florence was spared the wrath of the French army. Savonarola was now hailed as both prophet and saviour.

Comparisons between Trump and Savonarola have been made by others. Trump, like Savonarola, shrewdly exploited deeply-entrenched tensions in American political culture to promote his own ambitions by railing against a widely distrusted establishment. As David Frum observed in his book Trumpocracy: ‘Donald Trump did not create the vulnerabilities that he exploited. They awaited him.’ By fulminating against corrupt elites and fake news, his message appeals to ordinary God-fearing Americans who feel ripped off and disenfranchised from the American Dream. Trump’s promise to ‘drain the swamp’ and make America great again echoes Savonarola’s vow to cleanse Italy’s wickedness and transform Florence into a City of God.

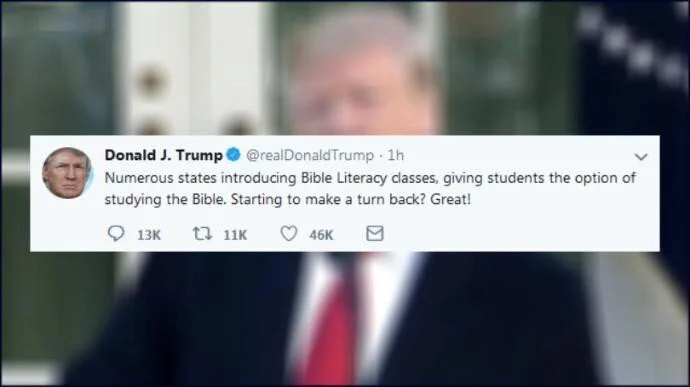

Donald Trump’s tweet supporting Bible studies in American classrooms.

Trump has also tapped into Christian fundamentalism to rally electoral support — first in 2016, and again in 2020 as he seeks to win a second term. Though hardly a figure known for piety, Trump can nonetheless claim a longstanding connection with a brand of Christianity that is perfectly compatible with right-wing evangelical politics. Trump is an adherent to the so-called ‘prosperity gospel’ movement, which claims that wealth and fortune are rewards from God. Trump had been introduced to this doctrine early in life when attending the services of Norman Vincent Peale, his family’s pastor in Manhattan. Peale’s memorable slogan was ‘prayerize, picturize, actualize’. His motivational book, The Power of Positive Thinking, tremendously influenced the young Donald Trump.

Trump’s political appeal to fundamentalist Christians explains the persistent Cyrus myth around his presidency. For his most zealous evangelical supporters, Trump is a ‘modern Cyrus sent by God to restore American greatness. They believe Trump is the ‘Anointed One’ who has come to deliver them from captivity by the liberal establishment that controls the country. His evangelical supporters are unmoved by reminders of Trump’s sinful past. They counter that Donald Trump is, like King Cyrus, a flawed vessel of God’s will. King Cyrus was a pagan king who liberated God’s Chosen People; and Donald Trump, an imperfect vessel anointed by God, will drain the swamp and make America great again.

But as Katherine Stewart, author of The Power Worshippers, has observed: ‘The great thing about kings like Cyrus, as far as today’s Christian nationalists are concerned, is that they don’t have to follow rules. They are the law. This makes them ideal leaders in paranoid times.’

In Renaissance Italy, Savonarola owed his rise to power to a pervasive climate of paranoia, fear, and fanaticism. After the expulsion of the Medicis, the swamp was drained. Savonarola quickly took control of the Florence’s Great Council and turned the city into a populist theocracy. It was a refreshing change after decades of the Medici oligarchy. There was, however, a darker side to Savonarola’s City of God. He passed laws prohibiting swearing and singing bawdy songs. Blasphemers had their tongues cut out. Homosexuality was severely punished. Christian shock troops called ‘Bands of Hope’ patrolled the streets and punished any sign of immodesty in dress or manner. The most notorious ritual was the infamous bonfire of vanities. Savonarola’s enforcers harassed people into handing over sinful possessions — books of poetry, cosmetics, perfumes, mirrors, masks, playing cards, dice, jewellery, musical instruments, nude paintings, sculptures, ornaments of any kind. The cursed objects were hauled to the Piazza della Signoria and tossed onto one of seven pyres, each representing one of the deadly sins, for a purifying incineration.

The new pope in Rome, Rodrigo Borgia — officially known as Alexander VI — was growing increasingly troubled by rumours of Savonarola’s claims of performing miracles, receiving divinations directly from God, and verbal assaults against the papacy. The breaking point came in May 1497, when Alexander VI played his most formidable card: excommunication. The Pope’s move proved effective in turning public opinion against the illuminated monk. Florentines had already been growing weary of Savonarola’s repressive theocracy. A riot erupted during his Ascension Day sermon. He was finally arrested for heresy and imprisoned. Under physical torture, or tormento, Savonarola confessed that he was a false prophet.

Sentenced to death, he was dragged to Florence’s main square dressed in a simple white tunic with head shaved and bare feet. At the same spot where bonfires of vanities once burned, he was hanged before a spiteful mob, the same Florentines who had venerated him as a prophet. On the scaffold, his limp body was dropped from chains attached to a cross and lowered into massive fire to be consumed by flames. One of the onlookers in the crowd was Machiavelli, who later drew lessons from Savonarola’s downfall in his classic book, The Prince.

The execution of Savonarola in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria.

In 1498, Savonarola’s fanatical theocracy was over after only four years. The Medicis returned to Florence and the humanist spirit of the Italian Renaissance continued to flourish. So did the extravagant Borgia papacy in Rome.

Donald Trump’s fate will be fixed not by excommunication, or impeachment, but by the American people when they go to the polls in November. While America burns, Trump is tweeting and posing with a Bible in a desperate attempt to appeal to the conservative and fundamentalist Americans who voted for him in 2016. He will continue railing against corrupt elites, and he will keep promising to make America great again. But the timing is not good for Trump. America is plunged into its worst crisis since the Great Depression — first by a global pandemic, now by a wave of violent protests transforming American cities into bonfires of vain hopes for a more just society.

If abandoned by the voters who once venerated him as a modern Cyrus, Trump will come to grief just as Savonarola did five centuries ago — scorned as a false prophet who made bold promises but failed to deliver. Yet even defeat will not likely extinguish the iconic status of Donald Trump in American political culture. After Savonarola’s death, his myth spread and a devoted cult grew around his name and legacy. If American voters reject Trump at the polls, many of his most fanatical followers will doubtless remain faithful to the cult of Trumpism.